Is deterrence in cyberspace possible?

Deterrence in cyberspace would allow for a solution to the absence of international legislation about the regulations that must be followed to lower the number of cyber-attacks. Today, this quasi-unregulated domain promotes the growth and usage of cyber weapons. While deterrence would not eliminate cybercrime, it would reduce the sophisticated, often covert attacks perpetrated by states or groups affiliated with those states. Although international accords exist, such as the Budapest Convention, which entered into force in 2014, they do not regulate the dangers of cyber wars, but rather attempt to control the phenomenon of cybercrime. The Paris Appeal of November 2018 does not contain legally enforceable standards, but it does encourage governments to act better in cyberspace and to limit malware spreading, among other things.

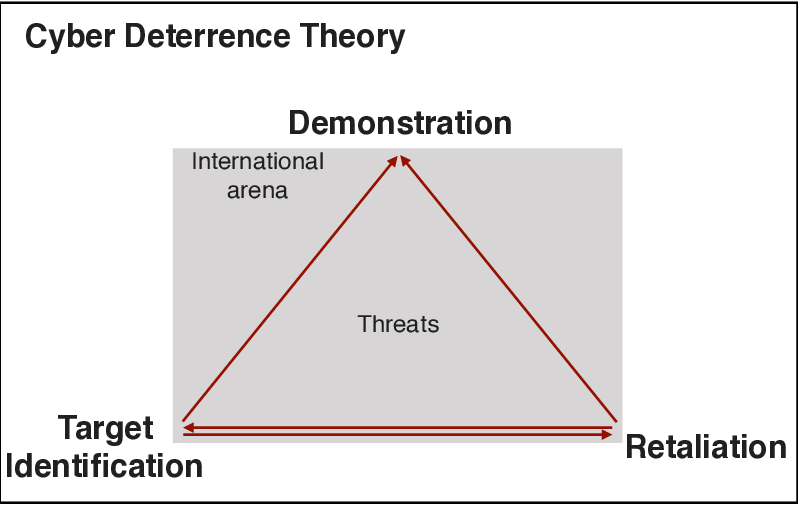

Cyber deterrence capabilities, in other words, sophisticated enough means to demonstrate the opponent that their strike would result in even more devastating retaliation for them, would therefore allow it to restrict the bellicose impulses of some powers in the absence of legal standards structuring and restricting the cyberwar that is being conducted. As a result, there are several reasons why governments should develop a cyber deterrence doctrine. However, there are various reasons why a true cyber deterrent cannot be successful and applicable in attempting to govern the ongoing struggle in cyberspace.

If deterrence theories have made it possible to foresee actions that would lead to a disastrous conflict in the ‘physical’ world with the employment of the atomic bomb since the cold war, these same ideas are now coming up against the very structure of cyberspace and therefore demonstrating its limits.

First, setting up a cyber deterrence necessitates being able to accurately attribute an attack and identify the attacker. Because cyberspace is immaterial and made up of grey zones, it appears to be exceedingly difficult to attribute an objectionable behavior in a specific way at the time. The attribution procedure is never a hundred percent trustworthy. The strategies employed by hackers to conceal themselves and leave few evidence make attribution extremely difficult. Technical assessments are no longer sufficient for attribution purposes since various actors employ the same techniques, tools, and operational methodologies in their activities. However, this attribution is required to go toward a judicial, political, or aggressive remedy, allowing for enhanced security in cyberspace.

Another issue is the response’s proportionality. The effects of the attack must be clearly recognized for the response to be legally legitimate and diplomatically just. However, determining the true impact of a cyber-attack, its scope and severity on information systems is challenging, especially because the impacts might last for years after they are introduced into a system. In the case of espionage, the harmful presence on a system is occasionally discovered years after the operation began.

Aside from knowing exactly how much harm to retaliate, the difficulty of regulating the impact of the retaliation is also tough to handle. As a result, carrying out the answer is challenging. However, to be credible on the world stage, to prevent the possibility of financial sanctions, for example, or to avoid escalating tensions, this concept of proportionality of response must be followed.

Finally, for the enemy to be aware of the country’s means of response and thus be credible, it is necessary to communicate directly or indirectly. Talking about methods in this environment includes communicating about tactics, known breaches in the enemy’s networks, or discrete preventative positions on its information systems. This means giving the enemy the possibility to improve its defense. This poses a real strategic and tactical problem. Given all of these concerns, an effective cyber deterrent based on the core concepts of nuclear deterrence theories does not exist today and is unlikely to exist in the future.

Sources:

- Aaron F. Brantly, ‘The Cyber Deterrence Problem’, (2018), https://ccdcoe.org/uploads/2018/10/Art-02-The-Cyber-Deterrence-Problem.pdf

- Stefan Soesanto, ‘Cyber Deterrence: The Past, Present, and Future’, (2010), https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-6265-419-8_20

- Will Goodman, ‘Cyber Deterrence: Tougher in Theory than in Practice?’, (2010), https://www.jstor.org/stable/26269789?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents